This is a multiple-part series. Join the email list to be notified when each article is published:

+ Why We Are Investigating the Link Between Fibroids, Keloids, and Hair Loss (And Why We Need an Illustrator to Do It). Read here.

+ CCCA Patient Education That Actually Changes Behavior: Moving Beyond "Stop Wearing Tight Braids". Read here.

+ Implication for Dermatology and Cosmetic Nurse Practitioners

+ Clinical Pearls: Key Teaching Points for Patient Education

+ DNP and PhD Nurse Scientist Research Ideas

+ Entrepreneurial Opportunites and Business Strategies

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia stands as the most common form of scarring alopecia affecting women of African descent, with prevalence estimates ranging from 2.7% in South Africa to 5.6% in the United States. To put that in perspective, if you're practicing in a community with significant numbers of Black women, statistically you're seeing CCCA patients every single week, whether you're recognizing it or not.

The disease typically manifests in the fourth decade of life, though women have been diagnosed as young as their early twenties and as late as their seventies. It begins insidiously, often with unexplained hair breakage concentrated at the crown. Patients describe their hair as feeling "different", more fragile, less resilient. They notice increased shedding, but what's falling out aren't normal-looking hairs. These are broken fragments, evidence of structural weakness occurring within the follicle itself.

The clinical presentation follows a characteristic centrifugal pattern, starting as a small patch of alopecia at the vertex and expanding outward in concentric circles. Early in the disease course, you'll see perifollicular erythema and subtle perifollicular scale, what is called the "gray halo" on dermoscopy. As the condition progresses, the inflammatory signs become less obvious even as the hair loss accelerates, leaving smooth, shiny, scarred scalp in its wake. By the time patients reach stage 4 or 5 on the Central Hair Loss Grading scale, they've lost significant areas of hair-bearing scalp, and the follicles in those regions are permanently destroyed.

Here's what makes CCCA particularly insidious: the progression of fibrosis occurs at a rate disproportionate to visible inflammation. In other primary cicatricial alopecias like lichen planopilaris or frontal fibrosing alopecia, you see overt inflammatory activity, redness, scaling, pustules, burning, itching. The inflammation announces itself. In CCCA, by contrast, patients often present with what appears to be a noninflammatory disease process resembling androgenetic alopecia. The scalp looks relatively quiet. But on biopsy, you find end-stage follicular scarring with only mild residual lymphocytic infiltration. The destruction has already occurred, silently and efficiently.

This discordance between clinical appearance and histopathologic reality has profound implications for treatment timing. By the time CCCA becomes cosmetically obvious, significant irreversible damage has already occurred. We're not catching this disease early enough, and our patients are paying the price with permanent hair loss that could have been prevented.

The histopathology tells the full story that the clinical examination only hints at. In early CCCA, you see perifollicular lymphocytic infiltration concentrated around the infundibulum and isthmus of the hair follicle, premature desquamation of the inner root sheath, and follicular degeneration. The inflammatory cells are predominantly T lymphocytes, suggesting an immune-mediated component to follicular destruction. As the disease progresses, you observe concentric perifollicular fibrosis, layers of collagen wrapping around dying follicles like a shroud. Eventually, the follicles are replaced entirely by fibrous tracts extending into the dermis. The sebaceous glands, which normally accompany hair follicles, are destroyed. What remains is scarred dermis with no memory of the follicular architecture that once existed there.

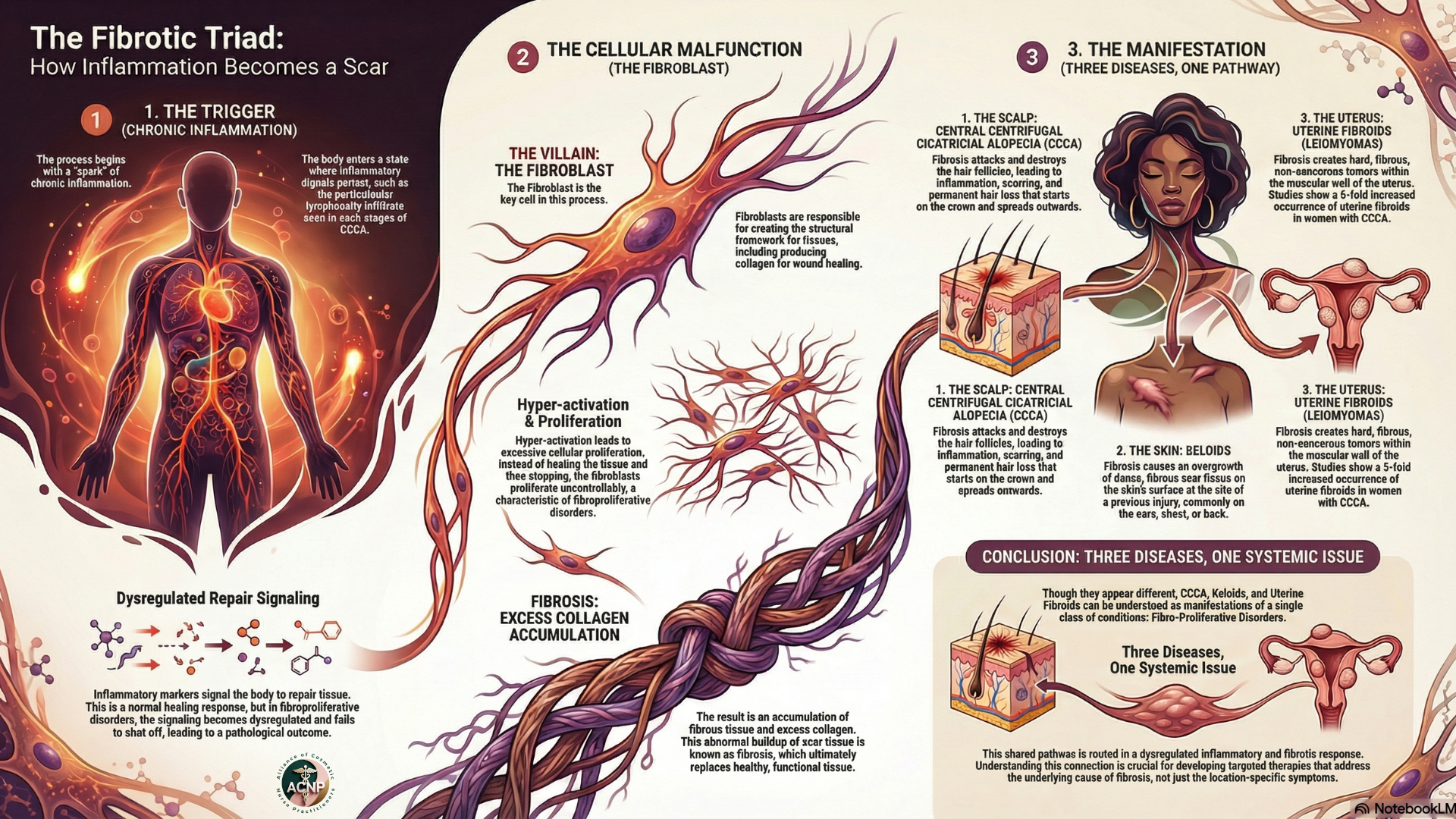

But here's where our understanding shifted dramatically: we used to think the inflammation was the primary driver and the fibrosis was simply the consequence. Recent molecular studies have completely upended that model. When researchers performed gene expression analysis on CCCA scalp samples, they found preferential expression of fibroproliferative genes, the same genetic signatures seen in keloids, systemic sclerosis, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The gene PRKAA2, which encodes for AMPK (adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase), was underexpressed by one-third in CCCA patients. This matters enormously because reduced AMPK activity is implicated in hepatic fibrosis and pulmonary fibrosis. The enzyme AMPK normally acts as a metabolic brake on fibrotic processes. When it's underexpressed, fibrosis proceeds unchecked.

This discovery connected directly to clinical observations we'd been making for years but couldn't explain. Women with CCCA have a five-fold increased occurrence of uterine fibroids compared to matched controls. They develop keloids at higher rates. These aren't coincidental associations, they're manifestations of the same underlying fibroproliferative tendency affecting different organ systems. CCCA, uterine fibroids, and keloids share molecular pathways involving dysregulated collagen production, abnormal extracellular matrix remodeling, and impaired regulation of fibroblast activity.

The genetic component became even clearer with the landmark 2019 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers used exome sequencing in 58 women with CCCA and identified mutations in PADI3 in 24% of patients. PADI3 encodes peptidyl arginine deiminase type III, an enzyme absolutely essential for proper hair shaft formation. This enzyme post-translationally modifies structural proteins like trichohyalin and S100A3 that give hair its mechanical strength and proper shape. When PADI3 is mutated, those proteins aren't modified correctly, and the hair shaft that forms is structurally compromised from the moment it's created.

The functional studies confirmed the pathogenicity of these mutations. CCCA-associated PADI3 variants resulted in reduced enzyme expression, abnormal intracellular protein aggregation, and dramatically decreased enzymatic activity. When researchers examined scalp biopsies from CCCA patients with PADI3 mutations, they found decreased expression not just of PADI3 itself, but of its downstream targets, the structural proteins that build hair. The entire molecular machinery of hair shaft formation was disrupted.

This genetic discovery explained something that had puzzled dermatologists for decades: why does CCCA predominantly affect women of African ancestry? The PADI3 mutations identified in CCCA patients are relatively common in African populations but rare in European populations. The minor allele frequency of the most common CCCA-associated variant (p.Thr286Ala) is 3.6% in African populations versus 0.01% in European populations. These variants persist in the gene pool because in heterozygous form, they cause late-onset disease with variable severity, evolutionary selection hasn't weeded them out the way it would a severely disabling childhood disorder.

But genetics alone doesn't cause CCCA. If it did, everyone carrying PADI3 mutations would develop the disease, and they don't. The genetic mutations create vulnerability, hair shafts that are more fragile, more susceptible to mechanical stress, more likely to break within the follicle. But the disease requires triggers, and that's where grooming practices enter the picture.

Here's the critical distinction we need to make: grooming practices don't cause CCCA in the sense that "hot combs" or "tight braids" are the primary etiologic agent. Rather, they act as triggers in genetically susceptible individuals. A woman with normal PADI3 function can wear braids for decades without developing scarring alopecia. A woman with PADI3 mutations may develop CCCA after relatively minimal mechanical stress because her hair shafts are already compromised at the molecular level.

When hair breakage occurs within the follicle rather than at the scalp surface, the follicular epithelium is exposed to foreign material, fragments of broken hair shaft. This triggers an inflammatory response. The immune system sees these keratin fragments as foreign antigens and mounts a T-cell-mediated attack. That inflammation, in turn, activates fibroblasts in genetically predisposed individuals whose fibroproliferative pathways are already primed for excessive collagen production. The result is progressive follicular destruction and replacement with scar tissue.

The disease demonstrates familial clustering with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, though with incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity. Published case reports document mothers and daughters both affected, siblings with varying degrees of severity, and three generations in single families showing the characteristic vertex alopecia pattern. This inheritance pattern indicates CCCA isn't a simple Mendelian disorder with one causative gene, but rather a complex genetic condition where multiple factors, likely multiple genes interacting with environmental triggers, determine who develops disease and how severe it becomes.

From a public health standpoint, CCCA represents an enormous burden of disease that's been systematically underrecognized and under-researched. The psychosocial impact of permanent, progressive hair loss in young and middle-aged women is profound. Hair represents femininity, cultural identity, self-expression, and confidence for many women. Losing it, especially to a condition that's often blamed on their own grooming choices, carries shame, isolation, and depression.

Yet despite affecting millions of women, CCCA research has been severely underfunded compared to other forms of alopecia. The breakthrough discoveries about PADI3 genetics, fibroproliferative mechanisms, and therapeutic targets have emerged only in the last five years. We're finally building the foundational knowledge base that should have been established decades ago.

Understanding CCCA as a fibroproliferative disorder with genetic susceptibility, triggered by mechanical stress and sustained by immune-mediated inflammation, transforms our therapeutic approach. We're no longer just trying to reduce inflammation with corticosteroids and hoping for the best. We're targeting the specific molecular pathways driving follicular destruction and fibrosis. We're intervening earlier in the disease course before irreversible scarring occurs. We're selecting treatments based on mechanism of action rather than historical precedent.

This represents a paradigm shift in how we approach CCCA, from symptom management to mechanism-based precision medicine. And the early results from this new therapeutic era are nothing short of remarkable.

We stand at a remarkable inflection point in CCCA care. For decades, this condition was dismissed, minimized, attributed entirely to patient "choices" about hair care, and relegated to the margins of dermatology research and education. Women who sought help were often told there was little we could do except try to slow progression with modest success. The message, implicit or explicit, was that this was their fault and their burden to bear.

That era is ending.

The research emerging over the past five years has fundamentally transformed our understanding of CCCA. We now know this is a complex condition with clear genetic underpinnings, driven by fibroproliferative pathways we can target therapeutically, sustained by immune dysregulation we can modulate with precision, and triggered by mechanical stress in the context of structural hair shaft vulnerability. We've moved from empiric treatment with limited rationale to mechanism-based interventions supported by molecular evidence.

And patients are experiencing the benefits of this knowledge revolution. Women who'd suffered progressive hair loss for decades despite multiple conventional therapies are achieving regrowth with topical metformin. Patients who'd been steroid-dependent for years are maintaining stability with JAK inhibitors while avoiding the long-term consequences of chronic corticosteroid use. Families receiving genetic counseling understand their risk isn't punishment for styling choices but biology they can manage with knowledge and appropriate care.

As nurse practitioners, we have the privilege and responsibility to translate this science into clinical practice. We're the ones building relationships with patients over time, tracking disease progression, adjusting treatments, celebrating victories, and sustaining hope through setbacks. We're positioned to integrate the latest research into frontline care faster than the academic dermatology world can update textbooks and training programs.

But our responsibility extends beyond individual patient care. We need to advocate systemically for the CCCA community. That means pushing for insurance coverage of effective therapies so cost isn't a barrier to treatment. It means demanding better representation of skin of color in dermatology research and medical education. It means calling out the historical narrative that blamed Black women for their hair loss instead of investigating the biological mechanisms driving their disease. It means elevating CCCA from a neglected condition affecting a marginalized population to a priority worthy of research funding, clinical trials, and therapeutic innovation.

The patients we serve have waited too long for this moment. They've endured not just progressive hair loss but the psychosocial trauma of being told it was their fault, the frustration of treatments that didn't work, the isolation of dealing with a condition their providers didn't understand, and the grief of permanent loss that could have been prevented with earlier intervention and more effective therapy.

We can't give them back the years lost to inadequate care. But we can offer them something powerful: evidence-based treatment that addresses the actual disease mechanisms, realistic hope for stabilization and regrowth, validation that this isn't about blame but about biology, and the expertise to guide them through a complex treatment journey with compassion and competence. The science has given us the tools. Our patients deserve nothing less than our commitment to mastering those tools and deploying them with precision, persistence, and profound respect for the women whose lives are transformed by the care we provide. This is the future of CCCA management. And it starts with each patient who walks through our door, trusting us to see them, hear them, and help them reclaim their confidence, their identity, and their hair.

I invite you to follow along this journey to improving the quality of life of a generation of women.

About the Author

Dr. Kimberly Madison, DNP, AGPCNP-BC, WCC, is a Board-Certified, Doctorally-prepared Nurse Practitioner, educator, and author dedicated to advancing dermatology nursing education and research with an emphasis on skin of color. As the founder of Mahogany Dermatology Nursing | Education | Research™ and the Alliance of Cosmetic Nurse Practitioners™, she expands access to dermatology research, business acumen, and innovation while also leading professional groups and mentoring clinicians. Through her engaging and informative social media content and peer-reviewed research, Dr. Madison empowers nurses and healthcare professionals to excel in dermatology and improve patient care.